Transactions are a key part to many modern databases, relational and non-relational systems alike. At a basic level, transactions allow us to treat a series of operations as a single unit. The reason transactions are so important is because they provide guarantees that developers can then use as assumptions when writing code. This means that there are entire set of concerns that you, the developer, don't need to worry about because the DB guarantees certain behaviors. This greatly simplifies the code and drastically improves its reliability.

What are these guarantees? You may already be familiar with the term ACID - atomicity, consistency, isolation and durability. From these sets of guarantees, “isolation” tends to be the most confusing, which is a shame because it is also the one where a deeper understanding directly translates to making better design decisions, and more secure SaaS.

I'm going to start by explaining what problem transaction isolation is even trying to solve. Then I'll explain the standard isolation levels as they appear in the SQL92 standard and are still mostly used today. Then we'll talk about the problems with SQL92 levels and how Postgres handles isolation and these problems today. Grab some tea and we'll start.

Why Transaction Isolation?

Let's take the classic transactional scenario, moving money from one bank account to another:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100.00 WHERE acctnum = 12345;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100.00 WHERE acctnum = 789;

COMMIT;

For reasons that should be obvious to anyone with a bank account, you really really want both updates to happen, or neither. This is what atomicity guarantees - that the entire transaction will either succeed or fail as a single unit.

While Atomicity provides important guarantees for a single transaction, Isolation guarantees come into play when you have multiple transactions running concurrently.

Suppose we have a scenario where one user ran the transaction above that moves money between accounts, and while that transaction was processing, but before it was committed, someone else ran select balance from accounts where acctnum=12345 . What will this query return? Does it matter if it executed before or after the first update?

This is what isolation levels address - how do concurrent transactions and queries affect each other. You can see why isolation can be more complex than atomicity - there are more ways concurrent transactions can interact. So let's look at how the database community approached isolation.

Transaction Isolation in SQL 92 Standard

Transaction Isolation levels were officially standardized in ANSI SQL 92. The ANSI committee started by defining the logical ideal of isolation. The ideal isolation as they defined it, is that when you have multiple transactions happening at the same time, the resulting state of the DB is one that is possible to achieve by running this set of transactions not concurrently, but sequentially. It doesn't state or mandate any particular order, just that one must exist. This level of isolation is called “Serializable” because it guarantees that a serial ordering of the transactions with the same results exists. It lets you think of the database in terms of atomic transactions happening one after another.

Serializable isolation is considered the gold standard in terms of correctness, but why is serializable isolation so great? Because this guarantee greatly simplifies the way you reason about your application and the way you will test it. You have invariants that you need your system to maintain, for example, an account balance can't go below zero. You can then check that each transaction individually maintains these invariants and serializable isolation guarantees that you don't need to worry about all the ways these transactions will interleave when they run in parallel. You can take transactions as entire units (as we did with atomicity) and only reason about the state of the system before and after each transaction.

Back in 92, the consensus was that serializability is a great ideal, but not something that can be implemented while still delivering adequate performance (spoiler: they were wrong). Since the ideal was not practical, they settled on suggesting multiple levels of isolation and explaining what can happen in each. The committee came up with a list of weird results you may encounter if you don't have serializability and called these “anomalies”. Then they defined the isolation levels in terms of “which anomalies can happen at each level”:

| Isolation Level | Dirty Reads | Non-repeatable Reads | Phantom Reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Uncommitted | Possible | Possible | Possible |

| Read Committed | Not Possible | Possible | Possible |

| Repeatable Reads | Not Possible | Not Possible | Possible |

| Serializable | Not Possible | Not Possible | Not Possible |

This is a practical approach and is useful for developers because it lets us say “I'm okay with some anomalies and I want more speed. Let me go with read committed”. So, as a responsible engineer writing an application with transactions, you should understand the anomalies and make informed decisions. Let's do that!

Isolation levels and their anomalies

Dirty Reads

The lowest level of isolation is read uncommitted. Read uncommitted allows a whole slew of anomalies, including the dreaded 'dirty read'. Dirty reads means reading data that has not yet been committed. Remember that if a transaction is not committed yet, it may never get committed. The user may change their mind, there may be an error, the DB can crash. Here's a simple example, lets say that we have two users who connected to the same database and each doing their work around the same time. In database terminology, the state of each connection is called a session, so we are looking at two concurrent sessions:

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

BEGIN; | BEGIN; |

| |

SELECT * from accounts where acctnum = 12345; | |

ABORT; |

In isolation level “read uncommitted”, if both these sessions execute concurrently, session B will see an account that does not exist with a balance that does not exist. It looked like it existed, but the transaction was rolled back - which means it never officially existed. If this query is part of a report about the total assets under management for the bank, the report will be incorrect and include non-existing assets.

It sounds so obviously terrible that you'd say who in their right minds would ever do dirty reads?

It is mostly useful in write heavy workloads where you want to support very high write throughput and don't care a ton if reports are not 100% accurate. For example for metrics. Because this level breaks the most basic expectations from transactions, many DBs, including Postgres chose not to support this at all.

Non-repeatable Reads

Non-repeatable reads means that the same query within one transaction can return different results if a parallel session committed in between.

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

BEGIN; | BEGIN; |

SELECT * from accounts where acctnum = 12345; | |

UPDATE accounts set balance = 500 where acctnum = 12345; | |

COMMIT; | |

SELECT * from accounts where acctnum = 12345; |

In isolation level “read committed”, the first query in the transaction in session B will return a different result than the second query, because the transaction in session A committed in between. Both results are “correct” in the sense that they reflect a durable state of the database, but they are different. You may think “why is this even a problem”?

The main problem with non repeatable reads is a classic anti-pattern known as “write after read”. For example, lets say that we want to give a 10% bonus to accounts with balance above 1000, and we use the following code:

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

BEGIN; | BEGIN; |

| |

UPDATE accounts set balance = 500 where acctnum = 12345; | |

COMMIT; | |

| |

END IF; COMMIT; |

The condition in session B was evaluated to true, and therefore we decided to update the balance in account 12345. But before we had a chance to update the balance, it was updated and committed by session A. The condition is no longer true, but due to the way the code is written, session B will still update the balance. The result will be a state that could not have happened if these sessions ran serially, and account 12345 will have an extra 10% bonus in their account that they shouldn't have gotten based on the desired logic.

There are a few ways to get around this problem without changing the isolation level. However, because "read committed" isolation level doesn't guarantee isolation between concurrent transactions as they commit, you need to be very careful about how transactions may interleave.

For example, since the problem occurs when data changes between statements, you may choose to do the entire update in a single statement:

UPDATE accounts

SET balance = balance * 1.1

WHERE acctnum = 12345 AND balance > 1000;

This will check the condition before updating each row, so the previous situation where a row is updated based on an outdated condition will not occur. However, this is not always the case! Consider the following statement:

UPDATE accounts

SET balance = balance * 1.1

WHERE acctnum in (

SELECT acctnum from accounts where balance > 1000)

Here the SELECT will run first and return all rows with balance over 1000. Then the updates run, a row at a time. Suppose that while it is iterating, another session updates account 12345 and commits:

UPDATE accounts set balance = 500 where acctnum = 12345;

When the first UPDATE gets to account 12345, it will see the new value, and again - account 12345 will get a 10% bonus on an account with a balance of 500, which is not what we wanted. Concurrent transactions can also easily lead to undesirable results if one or both sessions updates multiple accounts, like this:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts set balance = balance-100 where acctnum = 12345;

UPDATE accounts set balance = balance+100 where acctnum = 789;

COMMIT;

To prevent changes on rows that you intend to update without going to a higher isolation level, it is safest to lock the rows while selecting:

UPDATE accounts

SET balance = balance * 1.1

WHERE acctnum in (

SELECT acctnum from accounts where balance > 1000 FOR UPDATE)

SELECT…. FOR UPDATE locks the rows that it selects. In this example, other sessions won't be able to update the balance in any account while the update is in progress, preventing the inconsistency. Of course at this point you need to balance the performance implications of locks compared to the implications of using higher isolation levels. We'll discuss this in more detail when we talk about Postgres and its implementation of isolation levels.

A classic pattern for implementing job queues with Postgres uses FOR UPDATE locks to prevent multiple workers from picking the same job:

BEGIN;

SELECT job FROM job_queue FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED LIMIT 1

-- do stuff for the job

DELETE job from job_queue

COMMIT

Here, you pick a job from the queue and lock it for the duration of the transaction. When you are done performing the job, you delete it from the queue and commit. Other processes can use the same logic to pick jobs, while skipping ones that are already in progress. If you run this code in a loop, each SELECT will see which jobs are available when the select executes - since read committed isolation level allows you to see changes that were committed before the start of the transaction. But the FOR UPDATE lock will prevent other processes from picking the same job.

Read committed is the default isolation level in postgres and as a result it is the most commonly used one. If you understand the gotchas and handle them with well-placed locks, you can usually achieve correct application behavior in this isolation level.

Phantom Reads

With the non-repeatable reads anomaly, you can see changes to rows that existed when your transaction began. In contrast, with the phantom reads anomaly, new rows which did not exist earlier suddenly appear in the middle of a transaction.

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

BEGIN; | BEGIN; |

UPDATE accounts set balance = 500 where acctnum = 789; | |

SELECT * from accounts where balance > 0; | |

| |

COMMIT; | |

SELECT * from accounts where balance > 0; |

In isolation level “repeatable reads” both queries in session B will show the same balance for account 789. Because the update that was done in session A will not be visible to session B. However, the second query will also include account 12345 that was created by session A. This is a new row suddenly appeared in the middle of a transaction. This means that session B will produce an inconsistent report - both because it has two queries that returned different results, and because the second query shows the data that session A inserted, but not the data it updated.

Worth noting that you can also get phantom reads when a cocurrent session does an update that causes new rows to match a query. For example, if account 789 had a balance of -300 and session A updated it to 500, session B will see it in the second query but not the first.

Problems with the SQL92 isolation levels

The SQL92 isolation levels have a lot going for them - they are standard, they are not too challenging to understand, and they give developers practical tools to make good decisions in their design. No wonder they are still in use today. But they are also 30 years old and in some aspects, they show their age.

Some isolation levels became obsolete

Lets think about “Repeatable Reads” level for a second. Doesn't it look a bit weird? Transactions see a consistent view of the data that already exists, but new data just sort of shows up there. Why have a separate level just for this situation? The reason it exists is because when transaction isolation levels were introduced to SQL 92 standard, “repeatable reads” was the best level of isolation that many DBs could practically support.

These DBs implemented transaction isolation via shared locks. So when we did select * from accounts for the first time in a transaction, it took a lock on the rows we read. This doesn't block readers, but it blocked writers and delayed all updates until the transaction committed. This guaranteed that the data won't change while my transaction executes and the second time the same query ran, it will get the same values. Of course, you can't lock rows that don't exist yet. Therefore new rows will still show up. Leading to phantom reads.

As you can imagine, 30 years later, databases got better. Multi-version concurrency control, MVCC, became widespread and the most common implementation of transaction isolation in relational databases. Including Postgres. MVCC doesn't lock rows. What it does instead is keep multiple versions of each row (hence the name), and use those versions to isolate transactions. We'll discuss Postgres's MVCC implementation and how it impacted the isolation levels in the next section.

New anomalies were discovered

OK, so some of the isolation levels don't make sense any more, but at least we have Serializable which is defined as a logical ideal, and not based on implementation concerns. And if we run our DB in Serializable level, anomalies can't happen. Right?

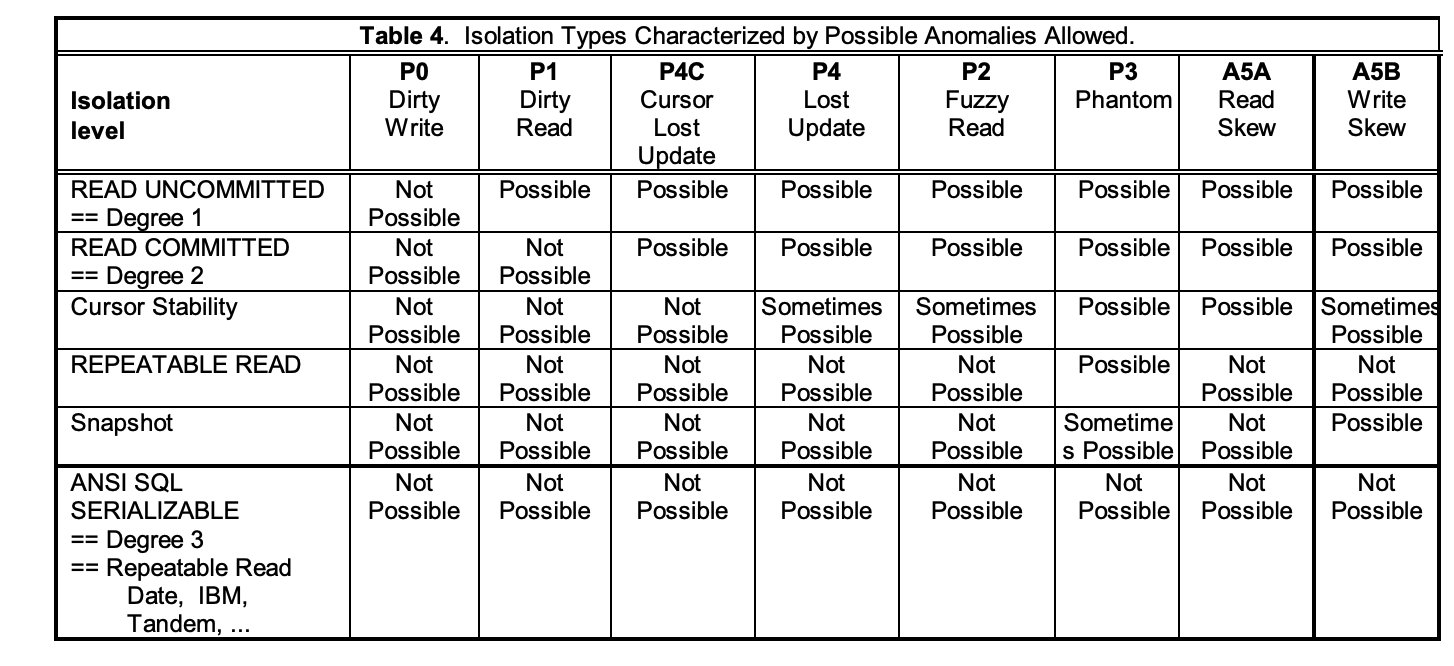

It turned out that defining a perfect state and then defining some states where certain anomalies can happen has this fundamental problem: There may be anomalies you didn't think of. So, only three years after the SQL92 standard came out, a very impressive team of researchers published A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels (1995). The paper introduced a whole collection of anomalies that weren't specified in the standard, and therefore were technically allowed at the Serializable level.

The result of the paper is an extension of the SQL92 isolation levels and anomalies with a lot more anomalies: Lost updates, dirty writes, write skews, read skews, fuzzy reads. And new isolation levels that handle these scenarios.

This paper, coming out after many relational databases implemented SQL92 isolation levels, led to the rather confusing state of things that we have to this day. Different databases support different isolation levels, and the same isolation level can mean different things in different databases.

Isolation levels in Postgres

Postgres handles the new anomalies without adding additional levels. It documented its behavior using the standard table with few notes:

| Isolation Level | Dirty Reads | Non-repeatable Reads | Phantom Reads | Serialization Anomalies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read Uncommitted | Allowed, but not in Postgres | Possible | Possible | Possible |

| Read Committed | Not Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible |

| Repeatable Reads | Not Possible | Not Possible | Allowed, but not in Postgres | Possible |

| Serializable | Not Possible | Not Possible | Not Possible | Not Possible |

As you can see, Postgres “repeatable reads” is equivalent to the SQL92 “serializable”. In fact, the current “repeatable reads” behavior was the behavior of “serializable” in Postgres 9.1 and earlier. This level is also called Snapshot Isolation (SI) or even “serializable” in other databases.

Postgres's serializable (also known as Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)) guarantees the “ideal” which is the emulation of serial execution of all committed transactions. It should be resilient to all known anomalies.

MVCC and isolation in Postgres

As we mentioned earlier, Postgres, like most modern databases, implements MVCC. In Postgres's MVCC implementation, when a transaction first writes to the database, it is assigned a sequence number called transaction ID or XID. When the transaction modifies rows, the original version of the row is preserved and a new version is added with this sequence number (you can see the current sequence if you run select txid_current();). Each transaction only sees the newest version of each row that is earlier than its transaction ID.

Let's take another look at one of our examples, and consider which transactions are visible to each session (note: I'm making some assumptions and removing some details for simplicity, see references for more detailed explanations):

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

BEGIN; | BEGIN; |

UPDATE accounts set balance = 500 where acctnum = 789; | |

SELECT * from accounts where balance > 0; | |

| |

COMMIT; | |

SELECT * from accounts where balance > 0; |

When session A and session B start their transactions, they both “take a snapshot” - record the highest and lowest IDs of currently active transactions (you can try this yourself with select * from pg_current_snapshot();). Let's say that they both see 190 as the lowest active XID. This means that transactions with higher XID did not commit yet.

In “repeatable read” and “serializable” isolation levels, both select statements in Session B will only show the data as it was committed when the transaction began - version 190 or lower. If you peeked at the Postgres buffer cache when both transactions started, but before any changes were made, you'd see something like this:

| t_xmin | t_xmax | acctnum | balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 0 | 789 | 3 |

t_xmin represents the xid of the transaction that created this row. And this row will be visible to both transactions since t_xmin is 125 and lower than 190.

When Session A performs its first update, it will be assigned its own XID - lets say 201. Both the new version of account 789 and the new account 12345 will have 201 as their new version. So if you peeked in Postgres memory after session A commits, you'd see something like:

| t_xmin | t_xmax | acctnum | balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 0 | 789 | 3 |

| 201 | 0 | 789 | 500 |

| 201 | 0 | 12345 | 100 |

You can see both the new version of account 789, and the newly inserted account 12345. Since they both have t_xmin 201, which is higher than 190, session B is not going to see either of the new versions. Its snapshot only shows the original version of account 789.

As you can see, using MVCC snapshots for transaction isolations means that the same mechanism that hides new versions of existing rows also hides new rows. Neither will show up in snapshots that were taken before those changes were made. A transaction with “read committed” isolation level will simply take a new snapshot at the start of each query and when conflicts are encountered - which means that each query will be able to see data from transactions that were already committed. Even if they did not commit at the start of the session.

Postgres's infamous vacuum process is responsible for regular maintenance and cleanup of all the different copies of each row: Getting rid of deleted rows that are no longer used and also performing a process known as “freezing”. The freezing process take rows that were last modified by the oldest transactions and indicating that they should always be visible. This process frees up these transaction IDs for reuse - very important since Postgres transaction IDs are limited to 32bit and you can't use more transaction IDs at the same time. This is why long running transactions and very frequent updates/inserts/deletes can cause issues with the vacuum process.

Performance implication of serializable in Postgres

In Postgres, “repeatable reads” level and “serializable” levels don't require additional locking since they are based on MVCC (implicit and explicit locks held by transaction in progress still exist, just like in "read committed"). Note that Postgres still has to track the rows that are modified by each transaction, as we'll see below, and it describes this tracking as “locks” but those are non-blocking and used for tracking and conflict detection.

Even without locks, serializable (and even repeatable reads) isolation can have performance implications for highly concurrent workloads. This is because transactions in both repeatable reads and serializable levels are more likely to fail and roll back due to serialization errors.

What are serialization errors? They look something like this: ERROR: could not serialize access due to concurrent update and they happen in a scenario like this:

| Session A | Session B |

|---|---|

| |

| |

|

The transaction in session A is attempting to modify a value that session B modified and committed after session A started and took a snapshot. Which means that session A is trying to update a value without being able to see its latest version. Which can lead to a state that would never have happened if the transactions ran serially (this anomaly is called a lost write). Therefore session A will get an error, the transaction will roll back, and session A can try again.

Worth noting that in this simple scenario, "read committed" will actually work correctly. Session A will lock the row and session B will wait until the lock is released, then see the new value and update it. And as we've seen, "read committed" will require explicit locks for correctness in more complex situations.

In a system with high concurrency and a lot of updates, the serialization errors in "repeatable reads" and "serializable" levels can lead to a lot of retries, which obviously have a negative effect on performance and require dealing with retry logic in the application. This is performance overhead that exists in addition to the extra checks and monitoring that PG needs to run in order to catch these issues, especially in serializable isolation.

The performance tradeoffs between “read committed”, where in order to maintain consistency you rely on locks - both explicit and implicit, and “repeatable reads” where you rely on failing conflicting transactions and retrying, are specific to each application workload. The advantage of “read committed” is that you can reduce the level of consistency in favor of better performance - the disadvantage is that you may reduce the level of consistency unintentionally and lead to incorrect results.

Transaction Isolation Testing in Postgres

As you already noticed, the Postgres developer community takes transaction isolation very seriously and hold themselves to a very high bar. Part of it is their isolation testing suite. It uses a method that IMO should be a lot more common in systems testing. You can find the code for the test suite in github and the README explains it well.

The core idea is simple and brilliant, like many things in Postgres:

The testers define different scenarios, just like the ones we demonstrated above. Session A does update and then commit, Session B does select and then update. You also specify the result you'd expect after all sessions and all transactions committed. The test framework then takes all the sessions and runs all possible ways these could interleave. One such run can be “A updates, then B selects, then A commits, then B updates”. Another can be “B selects, then A updates, then B updates, then A commits”. It then checks that the key invariants like “account 1234 has a balance of 500” are preserved in all permutations.

While PG isn't single threaded and there are other background processes that run, it is very close to deterministic simulation testing because the scenarios themselves with all the different combinations are serialized.

This kind of test framework means that when concurrency bugs are discovered and fixed, it is very easy to add a test with the exact scenario that uncovered them and to be sure it will be covered in the test.

To sum things up

Hopefully this post didn't leave you more confused than you were at the beginning. There is a lot of complexity when it comes to the behavior of concurrent transactions in different isolation levels. Serializable guarantees relatively easy reasoning - just imagine that all queries run serially, one after another. But as you saw, the main drawback is the possibility of rollbacks due to conflicts. Other levels require deeper understanding of all the anomalies. This understanding allows you to know whether the behavior provided in these isolation levels matches the business logic that you are trying to implement, and whether additional explicit locking is required. It will also allow you to make good performance tradeoffs. Techniques such as deterministic simulation testing can help catch and detect cases where concurrent transactions lead to incorrect results.

Last but not least, huge thanks to Alex DeBrie, Franck Pachot, Lawrence Jones and Gunnar Morling who reviewed early drafts of this blog, caught mistakes and improved the explanations. The remaining mistakes and confusing explanations are all mine. I also received substantial feedback that lead to an improved revision after the blog was published - thanks to Joseph M. Hellerstein, Justin Gage and Philipp Salvisberg.

Additional References:

- Transaction isolation in Postgres's documentation

- Internals of Postgres MVCC, in much greater detail

- Shorter and clearer blog on isolation in Postgres from Lawrence Jones

- Blog post explaining atomicity, isolation and MVCC in Postgres with snippets from Postgres source code

- Detailed blog showing various anomalies in postgres

- Blog by Franck Pachot showing unexpected issues with non-repeatable reads in postgres

- Great talk on concurrency and anomalies in Postgres

- Internals of the vacuum process

- Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) paper

- Serializable Snapshot Isolation in Postgres

- Great thread on monitoring the vacuum process

- The classic paper: A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels

- Paper with even more anomalies

- How transaction anomalies can be used to exploit web applications

- Project with tests that check isolation levels in different databases