This blog is based on the speaker notes for my talk at Data Day Texas 2023, and improved with feedback and ideas from my colleagues Ram Subramanian and Ewen Cheslack-Postava. If any of these missing database capabilities resonate with you and you'd like to try Nile's database, please sign up to our waitlist

Writing or talking about things databases don't do may sound a bit silly. There are obviously many things databases don't do. For example, I run many databases and not a single one of them made me coffee this morning.

It also sounds a bit useless. Knowing about things you can do is obviously useful

- it helps you do things. But what can you do with information about things databases tend to not do? Other than build a new database, that is.

Forewarned, forearmed; to be prepared is half the victory

In this blog, I'll point out functionality that is very often needed in data platforms and more likely than not, you will need to build yourself since your DB won’t handle it for you. Even though it really should. I know you will need to build all of this yourself, because I've seen it in almost every project I was part of over 20+ years.

You can take this list of things DBs don't do, and use it as a checklist for your application or data platform design - make sure you don't forget about them, because with high likelihood - you will need them.

In some cases there are some DBs that do these things. You can use this list to guide your choice of a DB. These things are not key criteria for choosing a DB, but if you have several close options, it may tip the scale.

And finally, it may be an entertaining rant to read. There is some relief in knowing that you are not alone in asking yourself "Why do I still need to implement this in every project? why doesn't the DB just take care of it?".

A Database can’t do everything - but a data platform could

Lets start with one thing that databases don’t do but everyone wishes they did and almost every vendor claims that they do:

If you pick a database, there will be a set of use-cases that it shines in, a set of use-cases that it is ok at, and some stuff that it was really not built to do. A good analogy is that of the grain of the wood. The grain of the wood is the way its fibers are arranged. When doing woodwork, if you work with the grain of the wood, the work will be easy and the result will be clean. If you work against the grain, the work will be difficult, the results will be of poor quality and you are likely to hurt yourself in the process. In a similar manner, if you work with the grain of the database - work with its architecture the way it was intended, your work will be easier and the results will be of high quality.

Unfortunately, pretty much every database vendor, at some point, claimed that their DB is good for everything. It is very tempting to believe them! It sounds so much easier to have a single DB for relations, documents, graphs, 5 year financial report, real-time location report of trucks in the app and the kitchen sink.

But the moment you dig into the details - who is going to run it, what are their priorities, how will they tune it, what hardware will it run on, etc - you discover that - shockingly! Different use-cases and different people have different needs and one-size really fits none.

Because one database can't be great at everything, we need data platforms. And for the most part, we need to build them ourselves for our specific use and vertical. However, this doesn't mean that we can't ask our databases to do a lot more - without going against their grain.

Things (Nearly) All Applications Need

Version Control for Schema Changes

What do you do if you need to change the database schema?

When I gave this talk at Data Day Texas 23, about 25% of the audience raised their hands when I asked "Do you just connect to the database with an admin tool and run alter table?". The other 75% likely use version control and migration scripts.

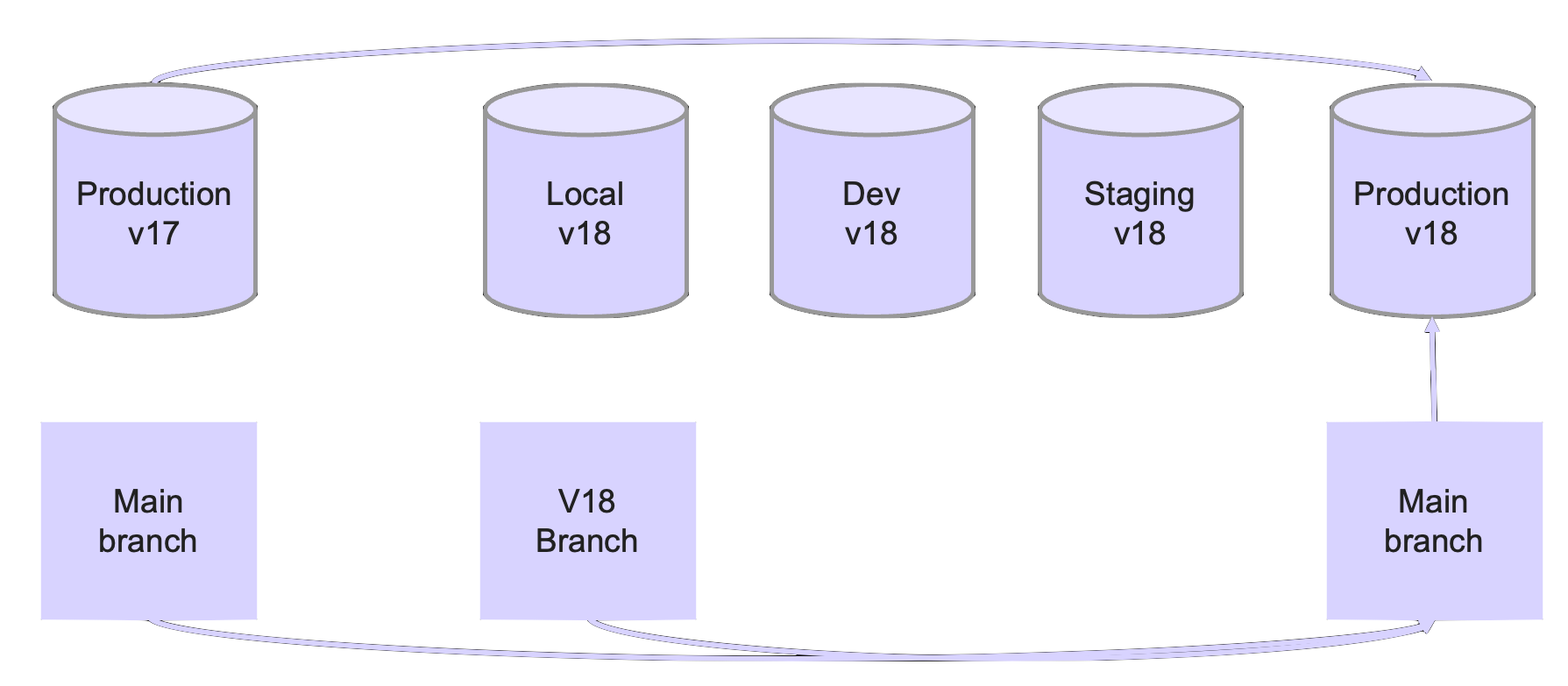

The migration script is a file with the DDL/DML of the changes you want to apply to the database schema. Developers typically test the changes locally, then post them to a source control system for someone to review. This usually happens in a branch and this branch can have many different changes related to a specific feature in it - both schema and application code changes. Sometimes the branch is deployed to a pre-production system for more validation, especially of dependencies and integration points. When it is time to take changes to production, the developer merges the branch with the changes and an automated system runs all kinds of tests before pushing this to production. Each engineering organization is responsible for all this automation - the deployment scripts, the tests, etc.

Databases are only aware of the current version of the schema that exists in them in a particular moment in time, and have the capability to apply the DDL/DML in the migration script. Sometimes even without too much locking or downtime.

But this is where database's assistance in schema migrations pretty much ends. Databases are not aware of compatibility considerations between the application code and the DB schema, so they will not help you catch changes that break compatibility.

In cases when you do need an incompative change, you'll need a thoughtful migration strategy. It will likely involve additional columns, indexes and views to allow application code to work with both the old and the new versions until the migration is completed. Most databases don't help with those more involved migrations. Many don't even support checking whether a column or a view is still in use and discovering who uses it. Marking columns or views as deprecated to warn current or new users is practically unheard of.

Ideally, a DB that would also be aware of multiple schema versions, allow us to flip between them and warn us before we push something incompatible to production (i.e. the main version used by the most critical applications).

When I presented this at Data Day Texas, one of the audience members asked about the feasibility of doing this: compatibility an application concern, so how will the DB detect compatibility issues?

One way to assess feasibility is to look at ways compatibility is already handled in less traditional data stores. There are multiple data lakes and event streaming systems that allow the developer to define the type of compatibility guarantee they want - forward, backward, transitive. Given this requirement, alter table operations can be assessed with known rules - dropping columns is rarely compatible, some type changes are compatible and others are not. This isn't rocket science. Marking columns as deprecated or tracking their usage is not beyond our current technical capabilities either.

More complex problems that are harder to detect automatically in the DB itself, like semantic changes, can be addressed by integrating the DB-level schema versioning with CI/CD and the various levels of tests that automated releases typically involve.

Once we go in this direction, there are more exciting possibilities. For example, running multiple schema in parallel on the same data, perhaps using schema on-write capabilities. This is great for both A/B testing and more gradual rollouts.

Tenant-Awareness

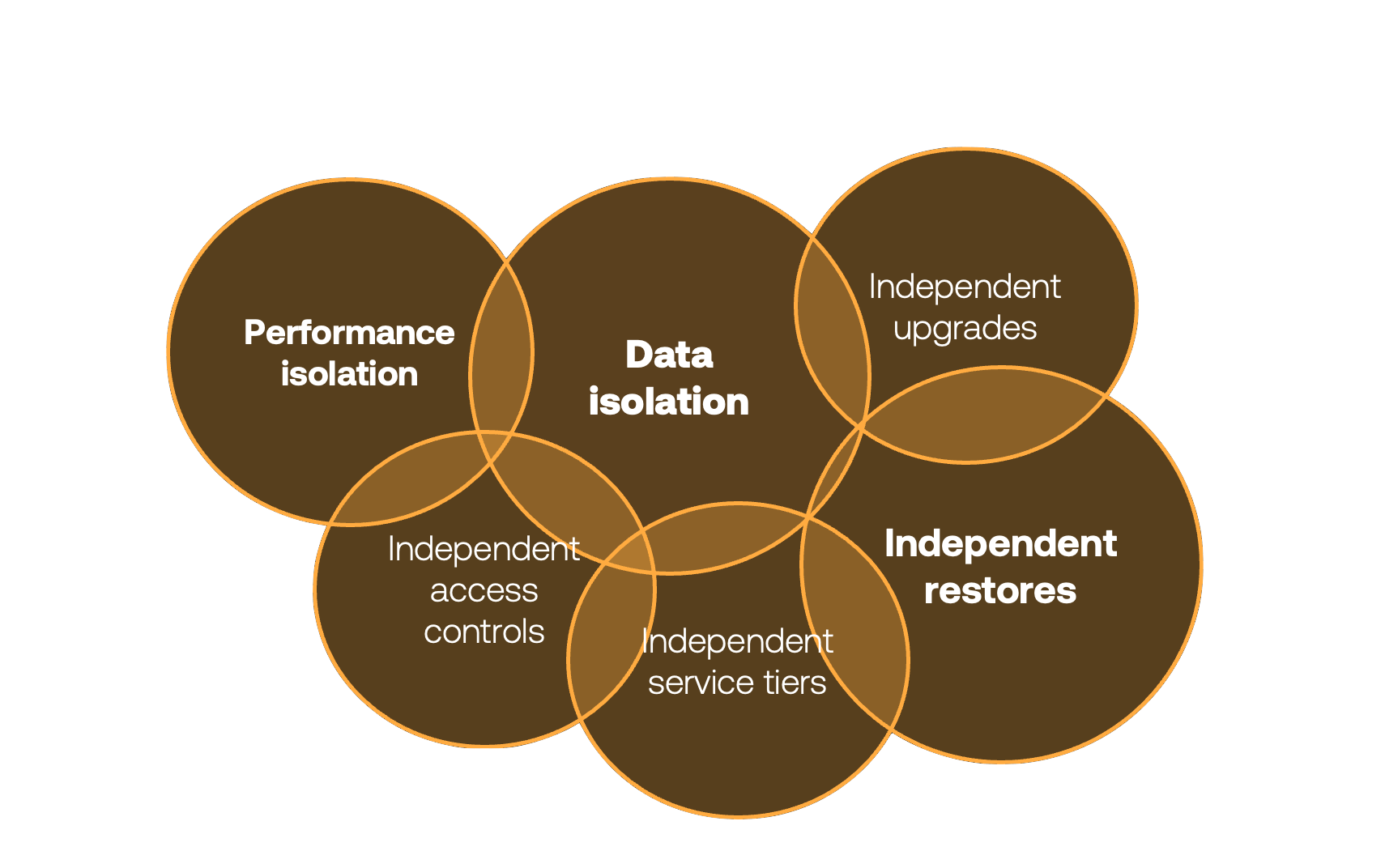

Production databases tend to contain data that belongs to someone else – your customers and users. And you typically need to isolate them from each other. You absolutely need to guarantee that no customer will ever see someone else’s data – this is critical and no mistakes allowed. Messing up this part will cost you the customer trust and may put the business at risk. But there is a bunch of other capabilities you will likely need.

All these capabilities are important, and it would be a separate blog or talk to get into all of these in detail. Independent upgrades and restores, for example, is something few companies think about in advance, and is hard to implement when it is actually needed. About a year ago Atlassian had multi-day downtime for some customers because they needed to roll back a change for a subset of their customers, and they had to go through a very manual process.

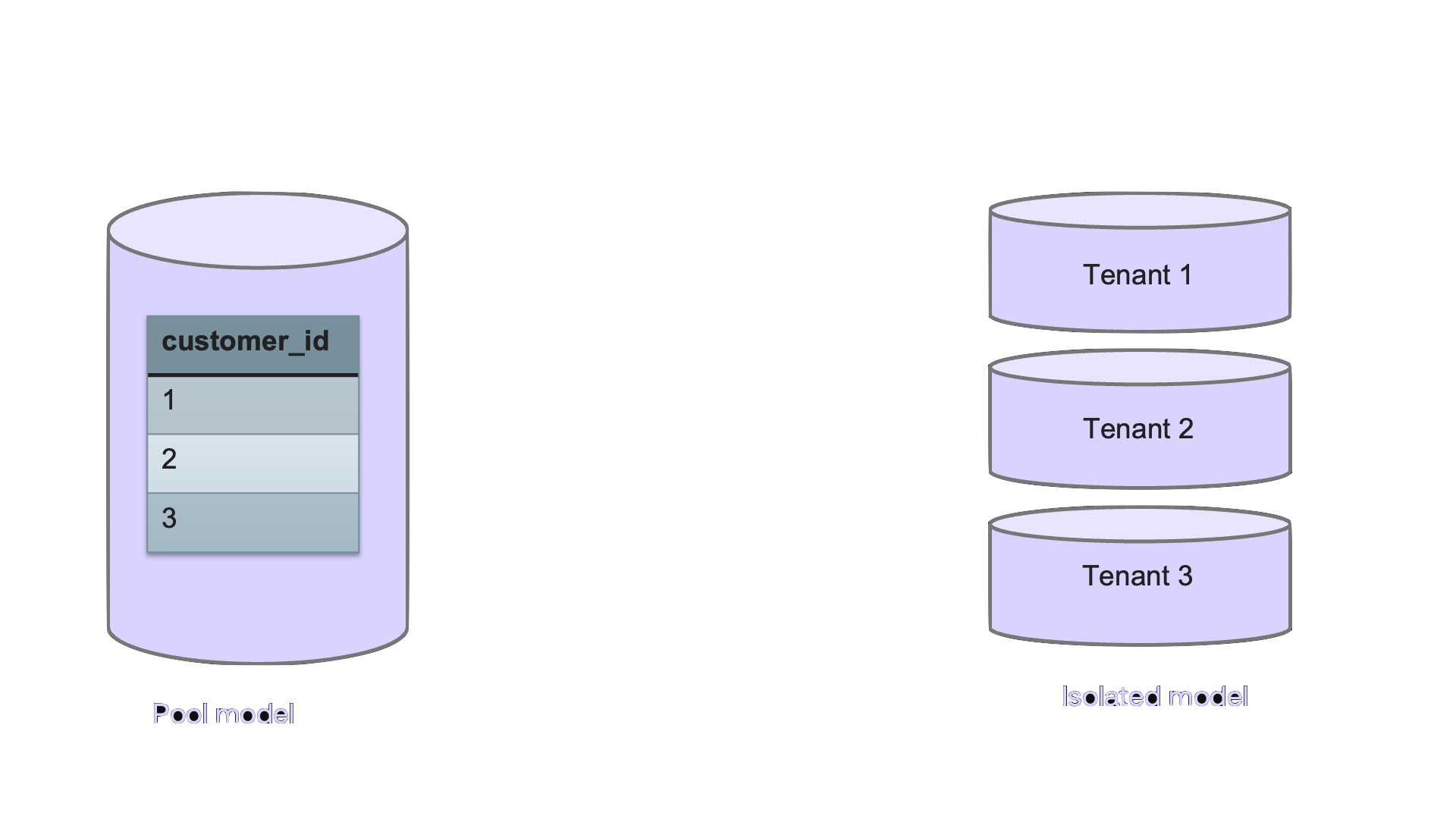

Since multi-tenant applications are so common, there are design patterns on how to model tenants in a database. The common models are either Isolated, where each customer gets a separate database, or Pooled where a single database is used for all tenants and each table has a column that maps to the tenant that owns the data. Generally speaking, the pooled model is more cost effective and scalable. But because databases don't actually do anything to support this model, it requires building a lot of the tenant-aware capabilities yourself and hope no one ever misses a "where" clause. The isolated model gives you all the tenant-aware capabilities "for free" but is challenging to scale effectively.

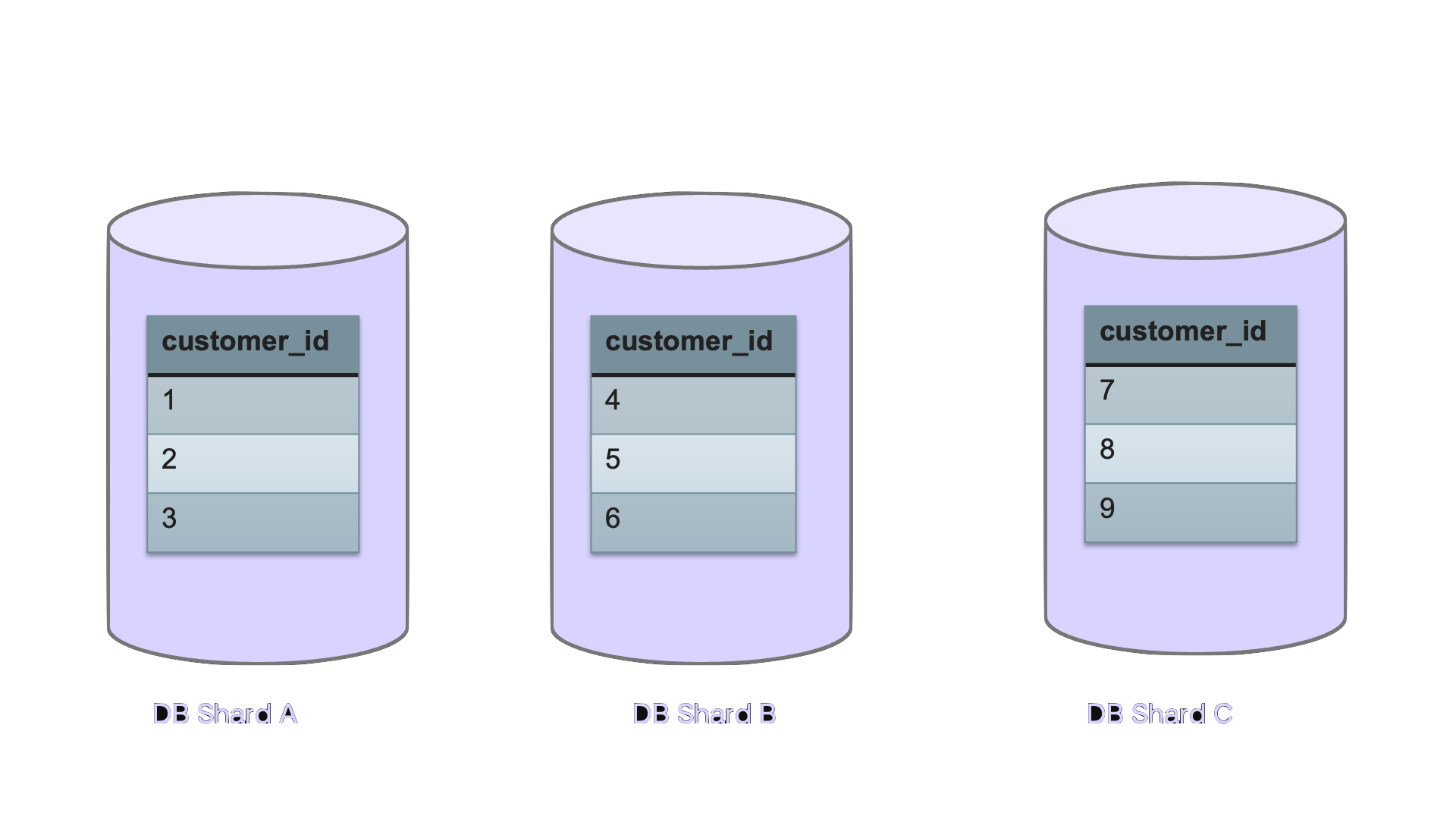

When you start with the pooled model, after a while you outgrow the capacity of a single DB or perhaps some of your customers require better isolation, better performance or better availability. So you end up sharding your database and placing different tenants on different shards. Depending on the extent to which your database supports sharding, you may or may not need to manually build a layer that determines the right shard for new tenants, directs each request to the right shard, adds new shards when needed and balances load between shards.

Democratizing Change Events

If you execute select * from my_table on your database, you only get the latest state of information in my_table. The records that exist right now. But DBs also have a record of all the changes that happened in the DB. All the inserts, updates, deletes. It is called a change log, redo log, write ahead log or a binlog - depending on your database.

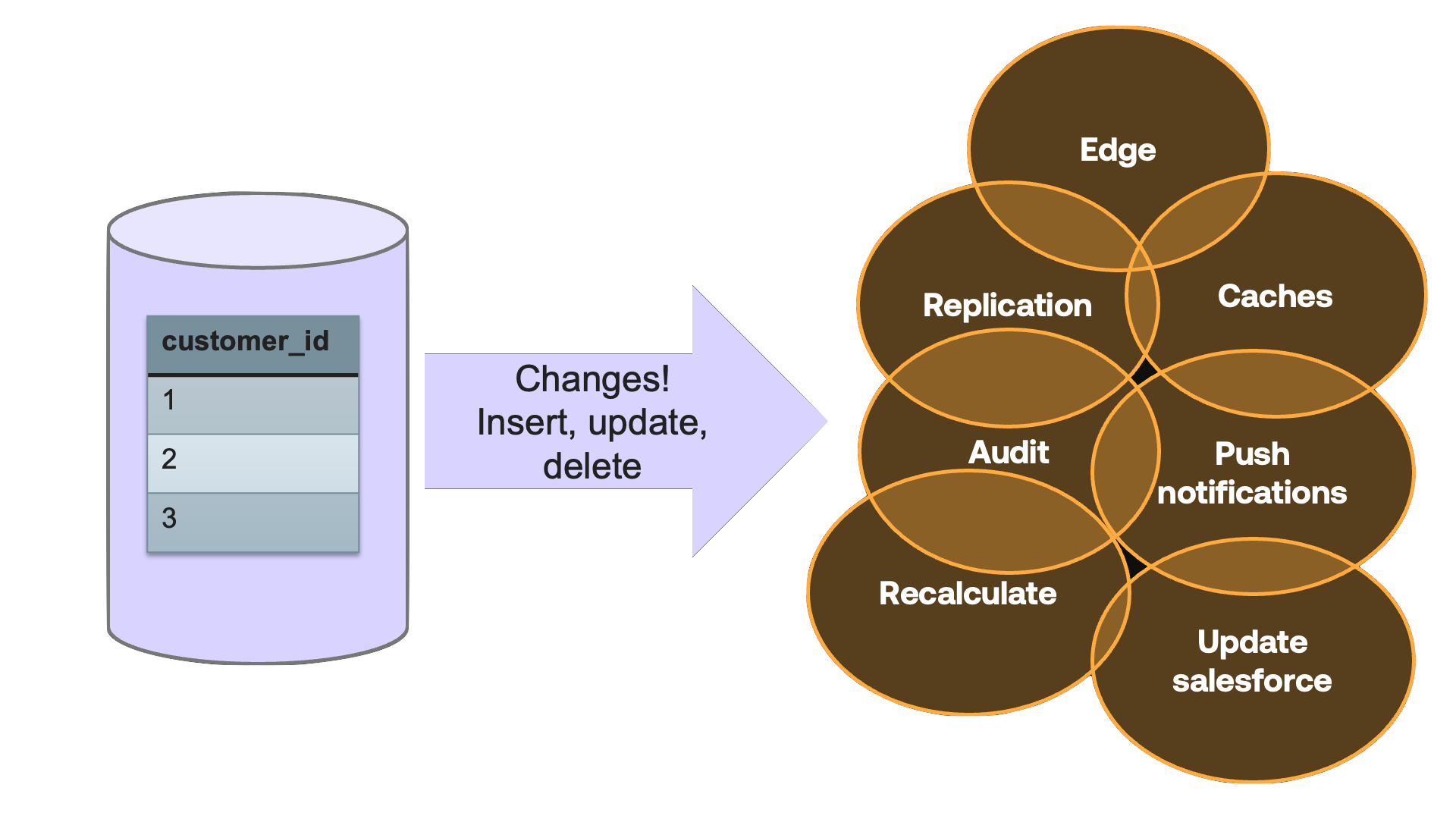

The historical record of changes in a database is very useful information, and you can build a lot of useful applications by listening or subscribing to change events.

Some databases let you perform some type of "time travel queries" where you run a query against an older state of the database. But this isn't the same as accessing the change events themselves, or getting notified about them when they happen. For change event use-cases, you would typically use Debezium to capture changes from the database, stream them to Apache Kafka, and from there use a combination of Connectors, Stream processing and Kafka clients to get the right changes in the right format to all these use-cases.

As you can see, those architectures aren't the simplest to build and maintain. They include multiple new components to learn, configure, monitor and troubleshoot.

In addition, in order to query the change history or listen to new change events, there are new clients and APIs that developers need to learn, in addition to the original database. This new ecosystem is not equally accessible in all languages and models. Web UI and FE developers in particular lack ways to access these real time events. Which is a shame because real-time updates are such an important UI feature.

Of course all those components also have their own security and access models. Remember the issue we mentioned earlier about isolating access to data between tenants? You now need to solve the same problem in the change capture system as well.

This pattern is so common and so many companies have implemented similar architectures... why is this not a normal part of the database?

Soft Deletes

You must have implemented this a million times when building apps. When a customer clicks “delete”, you don’t actually delete anything. Why? Because there’s a good chance that in the next 10 minutes, hours or days, they will call support and ask to get it back. Recovering the entire DB is a bit messy.

So instead, we have a field called “deleted” or “delete date” and when the customer clicks "delete", we update it. If the customer later calls support, we update it back. Much quicker and easier than a database recovery.

In many cases we do eventually need to delete the data for real. GDPR typically gives us 30 days to actually delete things. So we also write a process that does the real cleanup.

Now, you’ll notice that I wrote “We all did it many times”. So, why do we still do it? Why can’t databases add SOFT DELETE functionality? And maybe even add the cleanup job?

The annoying thing is that databases already do this internally. You’ve heard of “compaction”, “garbage collection” or “vaccuming”. These refer to a similar process – some DB changes involve a quick part that happens when you run the command and a part that happens in batches later. This design adds a lot of efficiency to many processes - especially deletes. So why not give all of us the same benefits?

APIs (In addition to SQL)

Databases, for the most part, talk in SQL. Pretty much every database that does not start out with SQL, eventually adds SQL. I’ve been through this at Cloudera, when we added SQL on Hadoop, then Confluent when we added KSQL and I now see the same demand in my own company. SQL has been the lingua franca of data for the last 40 years, and it seems well set to continue being this language for the next 40 years.

SQL is a great data language. But it is a terrible programmatic API. Why? Because it isn’t composable! Allow me to demonstrate.

Lets say that you have a table with user profiles, including their age and gender. Counting the number of users by age is a simple SQL:

Select age, count(*) from people

Group by age

And the same operation in Scala (with Spark's dataframes API):

ageGroup = people.groupBy(“age”)

print(ageGroup.count())

I'd say both are fairly readable, perhaps SQL a bit more so. But now lets say that we are working on a different method in the same module, one that requires counting only women.

In SQL, you'll write:

select age, count(*) from people

Where gender = 'female'

Group by age

Note that you can't really reuse the existing SQL or method. Either you write a new query, or if you really want to reuse another method, you need to do some creative string manipulation.

Meanwhile in Scala:

ageGroup = people.groupBy(“age”)

femaleOnly = ageGroup.filter(

col(”gender”).like(“female))

Print(ageGroup.count())

Print(fOnly.count())

The data APIs make it easy to take parts of the query and add more filters. Unlike SQL, these APIs are composable. And composability is key for reuse, minimizing redundancies and maintainability. This is why most developers use ORMs, even though there are many reasons not to use ORMs. SQL is not developer friendly.

If databases had native, optimized developer APIs, we wouldn’t need to trade off between maintainable code and performance.

Modern Protocols

The mismatch between databases and modern engineering goes deeper than just SQL. There is a big mismatch between the protocols applications use, and the protocols databases uses. And every project includes some engineering effort to work around this gap.

On one hand we have the database, which holds all the data, typically has its own binary protocol and uses LDAP or Kerberos protocols for authentication.

On the other hand, we have the browser. The browser needs to get data, so it can show it to customers. Browsers speaks in various HTTP-based protocols and typically authenticate with OAuth2 or SAML.

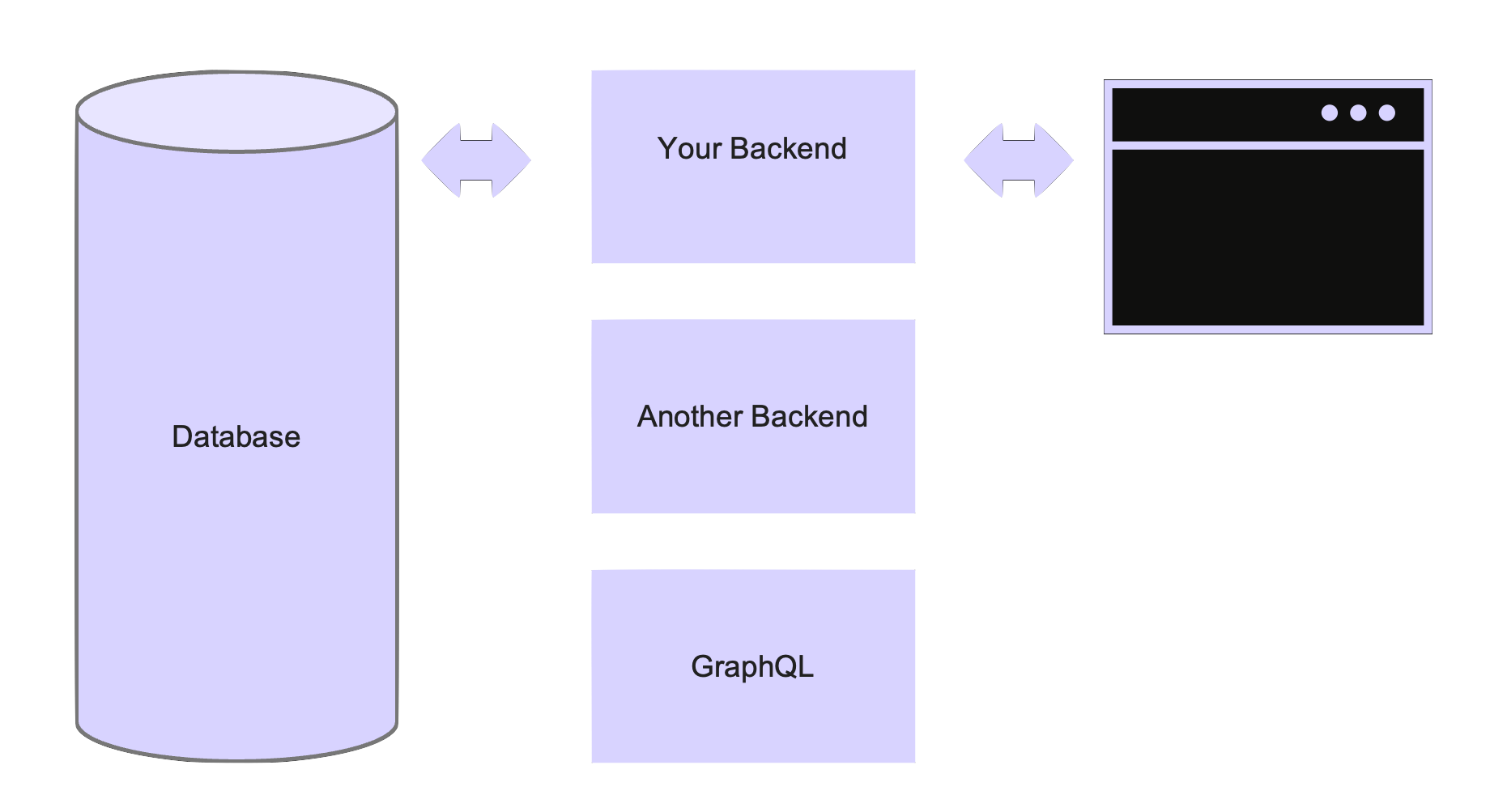

The mismatch seems pretty obvious - a system that only speaks HTTP needs to get data from a system with a native binary protocol. The solution is so obvious that we've been implementing is over and over for decades now - you write a backend.

The backend typically has a lot of important business functionality, but it also serves as a translator. It accepts HTTP connections from browsers on one side, and has a connection pool to a database on the other side. A lot of what a backend does is receive REST requests over HTTP, translate them into SQL and send them to the DB for processing, then get the result, translate it again and send it back. We all wrote a lot of code that basically does that.

In the best cases, this adds value. Maybe we abstract a bunch of internal DB details nicely. But in too many cases, there isn't much to abstract and the API pretty much exposes the table as-is. One use of GraphQL is to auto-generate APIs from a DB schema. I suspect that GraphQL so popular because developers tend to feel a bit silly writing another bit of translation code whenever a product manager wants another button in the UI. I'd argue that in some cases, it even introduces risk.

One way the backend can add risk is authentication. Users authenticates to your website, presumably with a standard secure protocol like SAML. But the DB doesn’t know about this user, the DB typically has service-account type of users that identify entire applications. So any kind of access controls need to be enforced by the application or with custom code in the database.

To make things a bit worse, it is a controversial but common practice to have more than one backend working with the same database. In these scenarios enforcing security in each backend introduces redundancy and even more surface area for problems.

If browsers could talk to the DB and users could authenticate to the DB with HTTP-based protocols, we'd have less low-value backend code that we need to test and maintain, the DB could enforce data access directly, reducing the surface area for access control issues. Combine this with a DB that is actually aware of tenant boundaries, and you get stronger guarantees for less effort.

DB Features from the Future

Global Databases

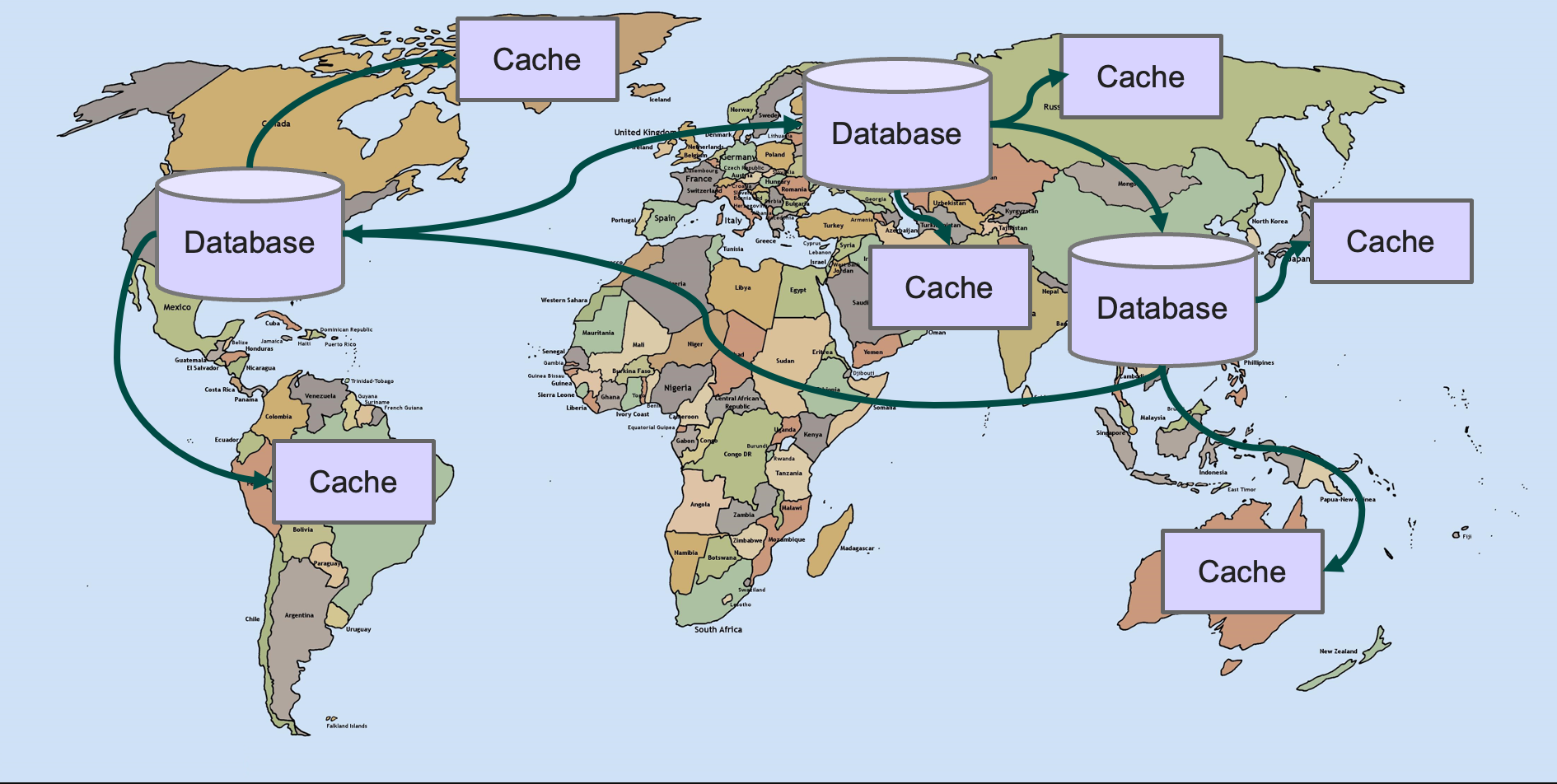

These days, even tiny companies find themselves with a global business. As a result, keeping all the data in one datacenter is no longer a feasible plan. Both data-related regulations and the low latency that users demand from their SaaS applications require globally distributed databases.

Typically this global distribution translates to having relational databases in 2-5 main datacenters, with selective replication between them. In addition to DBs in main datacenters, it is common to have a much larger distribution of caches that speed up performance of read operations.

Databases these days typically have several types of replication built in, which helps a lot in setting up the selective and async replication required between main datacenters.

Complying with regulations, on the other hand, is 100% on you. Which data are you allowed to copy? Who is allowed to access which data? How long are you allowed to keep it? You need to implement all those rules for each location in which you have either data or users.

When it comes to caches, developers are also left to their own devices. Keeping caches up to date while minimizing traffic is a challenging problem. And one that database vendors have only solved within the database.

In an ideal architecture, applications will not even know if they are talking to a cache or a DB. They will use the same clients to read/write and the data will be fresh when needed. The clients and infrastructure will route them to the best location.

Intelligent and Adaptive Databases

Tuning a database isn’t easy. Figuring out which indexes would improve performance and which indexes would slow you down is an important full time job in many companies. The indexes themselves are a series of tradeoffs – each database has a small collection of index types, each with its own benefits, problems and a lot of folk wisdom on when to use each..

We are starting to see proof-of-concept for databases that use machine learning to adapt to the access patterns and the data stored in them, and create indexes specifically to make the most common access patterns smarter. For example, a paper from Google that was published in SIGMOD 2018 titled "The Case for Learned Index Structures". Later research introduced additional index operations, join optimizations and query plan optimizations. It will be exciting to see a generation of data engineers focus more on building data products and data platforms that serve their users, and less time tuning indexes.

An area where I didn't find a lot of research, but seems to have a lot of potential for intelligence is capacity predictions. Can the DB predicts its own growth with high accuracy? If it can, perhaps it can also provision its own future capacity directly from the cloud provider and either migrate itself to a larger server or balance its load to new nodes in the growing cluster. These capabilities will give us a "serverless" experience because the DB would handle all those pesky servers itself.

Summary

This was just the tip of the iceberg as far as missing database features go. One could include tiered storage, better query optimization methods, more usable backup/recovery methods and built-in cronjobs.

While we shouldn't expect a single DB to be a perfect fit for any situation, we can and should expect databases to do a lot more for us.

Almost all the "missing features" that I mentioned here are necessary in most projects and many wouldn't require a complete re-architecture to introduce as an option in an existing DB. I believe that the reason every developer implemented these features again and again is that we've resigned ourselves to that reality.

Jeff Bezos famously said: "One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static – they go up. It’s human nature."

Technology keeps improving because users always ask for faster and better products. And when it comes to databases, we are the users. If we don't ask for more - we won't get it. In an age where Github Co-Pilot can write our boilerplate code and ChatGPT can write our CV, we can't just accept that soft delete, version control or reasonable data APIs are impossible.

Feel free to download the full slidedeck that I presented at Data Days Texas. If any of these missing database capabilities resonate with you and you'd like to try Nile's database, please sign up to our waitlist.